VJ Day

15 August marks the anniversary of VJ Day or Victory over Japan Day. The announcement of Japan’s surrender on that day in 1945 meant an end to hostilities in the Pacific and effectively marked the end of the Second World War.

Army aviation units stationed in the Pacific theatre included 656 Air Observation Post Squadron and three Glider Pilot Regiment Squadrons. Here we tell the story of two soldiers who were there.

656 Air Observation Post Squadron

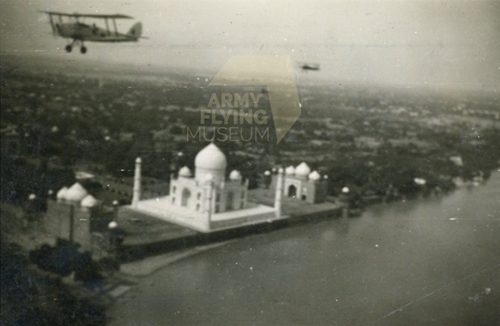

In August 1943, 656 Air Observation Post (AOP) Squadron sailed for India. British troops were amassing on the sub-continent in preparation for operations in Burma, modern day Myanmar, the following year.

The Squadron’s military role was summarised by 656 pilot Captain Frank McMath as follows:

“Our operational role was primarily to observe for, and to correct the fire of, the Artillery, and secondly to carry out all kinds of reconnaissance. … Our aircraft were Austers, piloted by Royal Artillery captains flying alone and serviced by RAF ground crews. Although this sounds a most complex affair, … in fact it always worked smoothly and with no trace of inter-service friction.”

After months of training and waiting for their aircraft, 656 Squadron was assigned to support the entire Fourteenth Army in their Burma Campaign. This meant that one aircraft was usually responsible for a complete division’s artillery fire. In January 1944, the Fourteenth Army started its move for Burma, only to be met by the Japanese invasion of India. By the end of 1944, the Japanese forces had been repelled and the Allied forces started their advance into Burma.

During the campaign, 656 Squadron was spread across a vast area, with aircraft stationed up to 250 miles from its headquarters at Imphal. On 4 May 1945, Allied forces took the city of Rangoon. Four days later, 656 pilots listened to Winston Churchill pronouncing Victory in Europe.

“We heard on the wireless that Germany had surrendered, and that the long-awaited Victory Day would be celebrated in England next day with a holiday and merry-making. Nothing could have seemed more remote from the actuality of our own war. Hemmed in for months past by the jungle, with the enemy on all sides, we had never been able to rouse more than a technical interest in the other war, and now that it had finished we felt little more than the anticipation of reinforcements and equipment for our next and harder battles towards the “Land of the Rising Sun”.”

Three weeks later the Squadron and the Fourteenth Army were relieved in Burma, and on their way to Madras to prepare for the expected invasion of Singapore and Malaya. On 6 August 1945 the first atomic bomb was dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima. Three days later, Nagasaki suffered a similar fate. Following these events and the Russian declaration of War with Japan, the Japanese government announced its surrender on 15 August 1945, VJ-Day.

Captain Edward W Maslen-Jones MC DFC RA

Captain Edward W. Maslen-Jones was called up in 1939 after the declaration of war. Eager for action, he volunteered for Air Observation Post flying training. Upon completion of the course he was posted to 656 Squadron and sailed with it to India in August 1943. As part of ‘A’ Flight, Captain Maslen-Jones took part in the Burma campaign and the Allied Forces’ move into Malaya. In January 1946 he was demobilised and returned to Oxford to continue his studies.

The main task of 656 Squadron was to observe and guide artillery fire from the air. One of the first targets Captain Maslen-Jones spotted were two tunnels used by Japanese forces, one of their entrances is seen above. Maslen-Jones described the tunnels later as followed:

“There were 2 Tunnels on the “road“ between Maungdaw and Buthidaung that passed through the Mayu Hills. In normal circumstances the Route would be considered to be the Trunk road between the Arakan coast, and the first main town inland. The obvious strategic advantages to the Japanese, of concealment of equipment, clandestine movement of troops, etcetera, were severely limited through constant [British artillery] attention to the … entrances.

… All 4 entrances were the subject of recorded Targets for our Field, Medium and Heavy Ante [sic] Aircraft Guns … Capt Frank MacMath and myself encouraged the Artillery Regiments to put down Harassing Fire whenever Time and Ammunition permitted.”

Replica medals of Captain Edward Maslen-Jones MC DFC RA. Maslen-Jones was one of only two AOP pilots awarded both a Military Cross and a Distinguished Flying Cross during the Second World War. The citation for the Military Cross reads: “It is no exaggeration to say that the success of the assault on Monywa (Burma) and the comparatively small casualties … are due in no small measure to the initiative, personal, continuous gallantry and devotion to duty which this intrepid young officer carried out his reconnaissance.”

The Glider Pilot Regiment

In January 1944 forces were gathered in India to establish the 44th Indian Airborne Division. The aim of the Division was to support British forces in Burma and Malaya, and possibly to undertake airborne operations against Japan itself. The Glider Pilot Regiment (GPR) was asked to contribute pilots and gliders for this new force but, due to large operations in Europe, only thirty men could be spared.

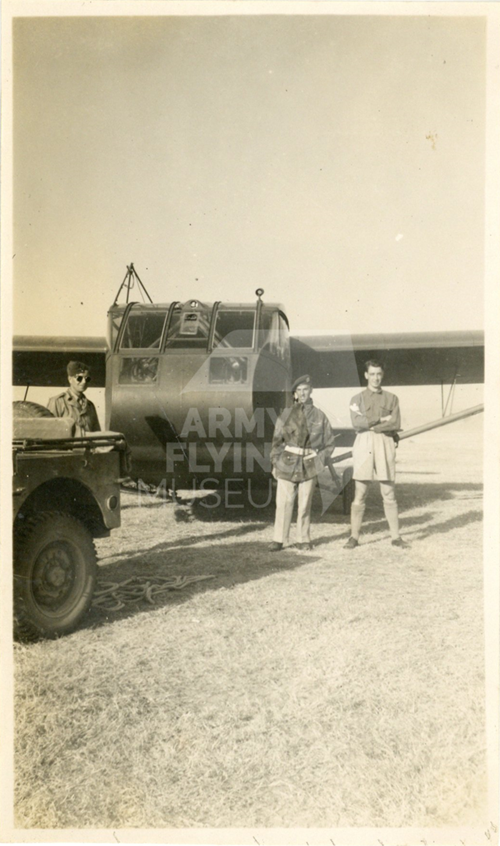

The ‘India Contingent’ of glider pilots was sent from Italy to India in early 1944. Their task was to train volunteers from local British units and the RAF to boost their numbers. After May 1945 and VE-day, a large group of pilots was sent from Europe to India to bolster the numbers. By July 1945 the small contingent had grown to six squadrons of almost 1,500 Army and RAF glider pilots stationed at four bases across Northern India.

Operating wooden gliders in the Indian heat and humidity proved difficult. Gliders were often unserviceable due to the heat affecting their structure and canvas. Pilots were kept up to date on their flying skills in Tiger Moth biplanes. Hadrian gliders had been shipped out to India in late 1944 along with some Horsa gliders. The later proved too heavy to be towed by Dakotas in the hot air and were not used until more powerful tugs arrived in mid-1945.

The planned operations involving the glider pilots included capturing Singapore, Bangkok and Sumatra, however plans were overtaken by events. At the surrender of Japan in September 1945 the operations were quickly halted. RAF personnel returned to their units and the remaining GPR servicemen were dispersed across India in ground roles. By mid-1946 all glider units in India had been disbanded and the remaining glider pilots had returned to the UK, often via a tour in Palestine.

The feeling at the news of Japan’s surrender was mixed. Wing Commander P C Price AFC, commanding officer of No.343 Wing, the glider element of Airborne Forces, in India described it as follows: “Although it was with a feeling of satisfaction that the news of Japan’s defeat was received, it was also with regret that the Wing had been unable to fulfil the task for which it had been formed and for which all personnel, aircrew and ground staff, had so earnestly hoped.”

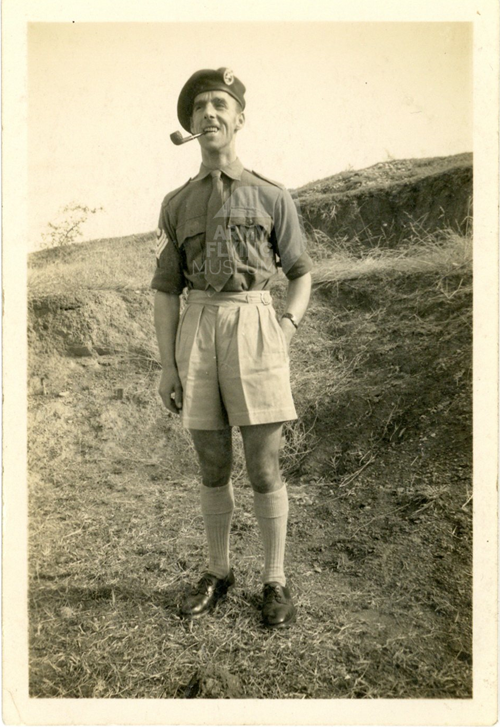

Staff Sergeant John Grice GPR

John George Grice joined the Territorial Army in 1939. He served with the Royal Artillery from where he transferred to the Glider Pilot Regiment. After completing his glider courses, he was posted to 1 Squadron in Italy in 1943. John Grice was one of the initial 30 glider pilots selected to go to India.

Upon arrival at Chaklala the pilots found that they would be sleeping under canvas and that there were very few gliders available and only one tug aircraft. Grice, together with Staff Sergeant Carline, was posted to the Glider Servicing Unit (GSU) at Bihta. The GSU assembled the American-made Hadrian gliders from crates. Grice and Carline’s job was to test these aircraft before they were sent to active squadrons.

“As we were doing this taking turns each day it tended to get a bit boring and Scoop Carline bet me that I wouldn’t do a loop. So on my next flight, after casting off at 5,000ft, I went into a stall. Then getting up to 150mph I gently pulled her up and slightly hung for a second at the top, then coming nicely over, as I still had plenty of height I continued with two more loops each one being better than the first. After landing I felt really chuffed. Of course Carline wouldn’t let me get away with that. So on his next flight after cast-off he proceeded with his effort and succeeded in doing five loops one after the other.”

Following their test-flying duties, Grice and Carline were posted to 670 Squadron at Fatejang in mid-1945. They taught conversion courses to RAF pilots that had been flown out from England to make up for the glider pilot shortage in India. Grice: “We were now doing plenty of training, ready for the final fling against Japan, but of course the Atomic bomb saves us the trouble.”

Staff Sergeant John Grice returned to England at the end of October and was demobilised from the Army in 1946.