The Korean War

Between the years of 1950 and 1953, a brutal and bloody war was fought between the North and the South of Korea. It was one of the most destructive wars of the modern era with millions of soldiers and civilians being killed or wounded. The war started when the North Korean, Communist forces, who were backed by China and the Soviet Union, invaded South Korea, who were supported by the United States (US).

To oppose the invasion, the US deployed its military which was soon joined by contingents of the United Nations (UN) including those from the British Commonwealth. Around 28,000 British troops served in Korea along with forces from South Africa, Australia, India and other Commonwealth countries.

The first year of the war saw a series of fast-moving offences and counter-attacks which ran along the whole length of the Korean mainland. However, by the time that Light Aircraft Flights were requested, the fighting front had stabilised somewhat and both sides had dug-in for a campaign of trench warfare in which artillery played a decisive role. The mountain terrain meant that an Air Observation Flight was vital because observation was hindered at ground level. In order to overcome this issue, the recently formed 1st Commonwealth Division was sent two Royal Air Force (RAF) Light Aircraft Flights.

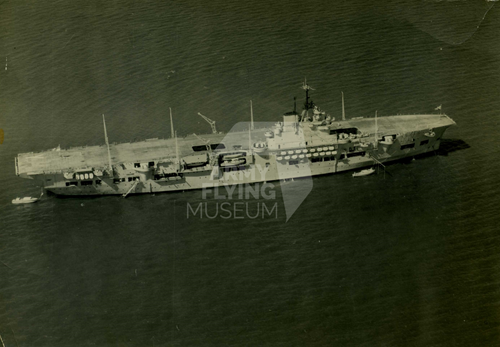

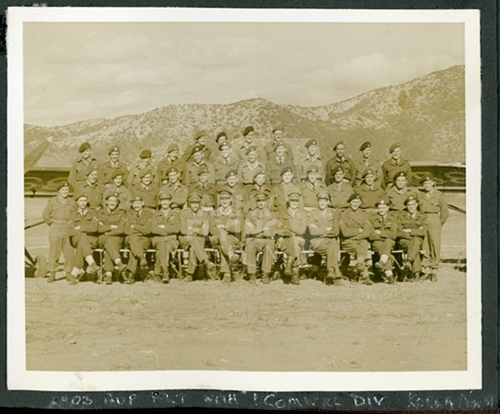

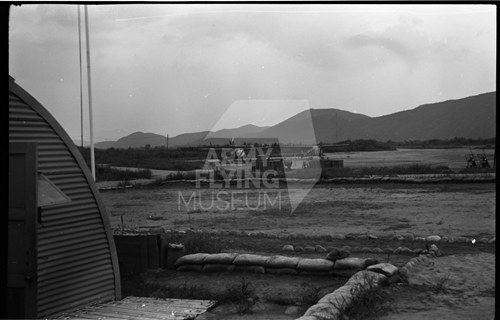

The first flight to arrive was 1903 Independent Air Observation Post Flight RAF. This Flight had been based in Hong Kong and was transported to Japan in July 1951 on board the aircraft carrier HMS Unicorn. Soon afterwards, the Flight was sent across to Pusan in Korea onboard a Short Sunderland Flying Boat of No. 205 Squadron. They began their flying operations in early August 1951, making use of their five Auster Mark 6 aeroplanes which were flown by six Royal Artillery officer pilots. Along with the pilots there were around forty RAF technicians and Royal Artillery drivers and signallers. Originally, the Flight was stationed at Airstrip AE111 but in August they moved to Fort George on the Imjin River.

The primary task for these pilots was to observe and direct artillery. 1903 Flight primarily carried out this role for the UN forces. These shoots took place from several thousand feet up and day sorties would range in duration from one to three hours. The pilots would use this time to spot enemy positions and, once the attacks were carried out, assess the artillery bombardment’s effectiveness. Typically, the last sortie of the day was used to look for unusual enemy movement which could suggest when or where future attacks would take place. According to Lieutenant Colonel Derek Jarvis (retd) in his book, Flying an Unarmed Auster for the Royal Artillery in the Korean War:

“The pilot would take off about an hour before dawn, so as to be over the target at sunrise. Many sorties, particularly if there were enemy assaults, carried on after dark and the pilot only returned when he could no longer see targets or gun flashes.”

Alongside these artillery sorties, 1903 Flight provided photographic reconnaissance, as they could take oblique and vertical aerial photographs. These images could then be used to help infantry commanders to plan their attacks.

The decision to create a new flight to carry out air observation tasks was taken for a few reasons. Lt Col Derek Jarvis also gives one such example:

“We found that there was an enormous demand on us for providing liaison flights for senior officers, which took up a lot of flying hours, which we could ill afford. Consequently, a new flight was formed: 1913 Light Liaison Flight RAF, which joined us at Fort George.”

Both these flights also helped to undertake the large amount of tasks which were required by the US and Commonwealth forces. These included reconnaissance and observation, movement of men and materiel, and photography. The later involvement of 1913 Flight was crucial as it applied more men to these tasks, meaning that 1903 Flight were able to concentrate on directing the fire of 2 Royal Canadian Horse, 14 Field Regiment Royal Artillery, and 16 New Zealand Field Regiment.

1913 Flight’s six pilots were from the Glider Pilot Regiment and flew Auster Mark 6’s. In January 1952 they were also provided with a US Army Cessna L-19A ‘Bird Dog’ and, in November of that year, they were given an Auster Mark 7. The Cessna was acquired to ferry around VIPs, especially Major General James Cassels of the GOC Commonwealth Division, who is said to have sworn never to fly in an Auster again after he was involved in a crash landing. The Cessna was used by 1913 Flight as their VIP transport for the rest of their time in Korea.

Throughout the course of both Flights’ operations, UN air superiority was maintained. Despite this, both Flights still suffered personnel losses as two pilots and two of the groundcrew were killed. Anti-aircraft fire and artillery shells were the cause of two of these casualties. Two further pilots and a rear observer were shot down and captured as well. The Commander of 1903 Flight, Major Wilfred Harris MC was also killed on 2 June 1953, when a damaged American F-84 Thunderjet crashed onto the Fort George airstrip and hit his jeep. There were several occasions where US aircraft crashed on the airstrip, as it was conveniently located for them to use as an emergency strip.

Nearly two years after 1903 Flight began operations in Korea, a ceasefire was agreed between both sides. After this came into effect the role of 1903 Flight became focused on visual reconnaissance. Some sorties were carried out over the Demilitarised Zone and the Chinese lines. Both flights remained in Korea for another eighteen months and over the course of the following year they were still carrying out photographic sorties and practice artillery shoots, as well as patrolling the Demilitarised Zone.

In January 1955, both flights returned to the UK. The role played by the two Flights was crucial to the campaign’s success. Throughout the war, 1903 Flight carried out almost 3,000 Air OP sorties, whilst 1913 Flight carried out around 9,000. Their valuable contribution can be seen through the large number of gallantry awards received compared to their size. These include a Distinguished Service Order and a number of Distinguished Flying Crosses.

Exhibition created by Henry Whitington, Archive Assistant, 2021