Operation MARKET GARDEN

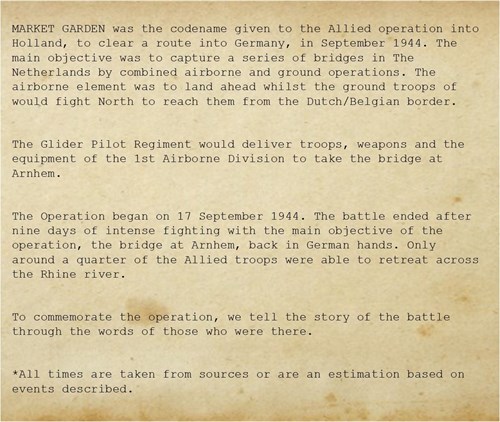

16th September 1944 08.30hrs

I received a signal telling of the birth of my daughter! The drill was that after briefing, everyone was confined to camp, but I decided to take a chance, and to my surprise, the O.C gave me ten hours leave, and I did it, with half an hour to spare!

16th/17th September 1944 00.00hrs

We’d heard it all before but we went through all the administrative motions and completed loading the gliders. By midnight on the 16th, there had been no postponement, no cancellation. But there would be. There always was.

17th September 1944 06.30hrs

We woke early on Sunday, the 17th September – still no cancellation, so we shrugged our shoulders and thought ‘Well if it is on, let’s get it over with and get home for next week-end, like we did from Normandy’.

17th September 1944 11.00hrs

Combinations of glider and tug aircraft stretched away in front as far as the eye could see. About half a mile away, another long stream, keeping parallel to us, until it was time for them to break away to another objective.

17th September 1944 11.00hrs

There was coffee laced with rum, the last drink that many would have on this beloved earth of ours. How many would die? How did I feel myself? As I settled in my seat and adjusted my straps, I looked back over my shoulder at the faces of the men behind me.

17th September 1944 12.00hrs

As we thundered for home we could see streams of combinations still coming, in an unending line. Leaving the Dutch coast, everyone heaved a sigh of relief and chatter came over the intercom like a women’s tea party in full session.

18th September 1944 10.00hrs

This morning we set off down the road to Arnhem. German resistance is getting harder. It is a war of vicious sniping and ambushing. We have just filled a jeep with ammunition and packed it with armed men for an attempt to dash through.

18th September 1944 14.31hrs

We sat there for a moment, looking pleased with ourselves when the crackle of distant machine guns and the whistle of some nearer shots that were obviously meant for us, reminded us forcibly that this time we were not on an exercise.

19th September 1944 15.30hrs

They seemed to give us everything but the proverbial kitchen sink. In this hopeless situation Sgt Ross ordered to take the table cover off the kitchen table and go outside with it. This effecting our surrender.

19th September 1944 19.00hrs

Dear Mr & Mrs Hooper, before we took off Jimmy asked me to drop you a line. There is no need to worry; it was really a “large piece of cake”, everything went like clockwork.

19th September 1944 20.00hrs

Dusk began to fall and with it my spirits fell too. I had no one to talk to and I fell to thinking most despondently. The rattle of machine gun fire became more intense. Any moment I expected to hear a shell crunch into our house.

19th September 1944 22.00hrs

We moved out to Oosterbeek park and dug ourselves in, but it was very thinly held. I was separated from Simion, he was in a foxhole about fifty yards from mine, all through the night we were mortared.

20th September 1944 17.00hrs

Nothing is worse than seeing comrades killed and even more distressing than the outcries of pain from the wounded was our inability to do much for them other than dress their wounds with our field dressings.

21st September 1944 11.30hrs

We moved into the position at Oosterbeek just before midday on the 21st September. One glance and we knew that it was untenable, even if there hadn’t been the bodies of those killed here before us and the wounded to remind us.

21st September 1944 15.00hrs

The Germans have brought up a loudspeaker van and are calling us to surrender. They say only 3,000 of your Division are left. We fired at it and a bunch of glider pilots are yelling their heads off swearing abuse in reply to the surrender idea.

21st September 1944 16.00hrs

There was little inclination on anyone’s part for conversation, for it was best to leave unsaid the thoughts universal in every mind. Where was the Second Army? When would they come? How much longer could this go on? What had happened at the bridge?

22nd September 1944 15.00hrs

I would think as a more experienced soldier, I might have thought more about the situation, but to me at that time, we were given a job to do and we were doing it and this was war.

23rd September 1944 14.00hrs

I had one magazine left for my trusty Tommy gun but food and water were problems. In the afternoon, the sun shone and the Germans mounted the heaviest attack yet on our positions. Our manpower was, by now, about a third of what we started out with.

24th September 1944 09.00hrs

Dead tired Tommies, filthy dirty, and unshaven came to our kitchen to heat up food and water for tea. They were fighting from small slit trenches and complained about the air bursts, which caused gruesome casualties.

25th September 1944 21.01hrs

It was exactly nine o’clock. At that very moment all hell broke loose and a shower of mortar bombs dropped on the common where we were standing. Vivid flashes of flame lit up the sky and there were terrific explosions.

25th September 1944 21.30hrs

My second-pilot, Johnny Gittings, survived this final obstacle and was checked in by me at our evacuation assembly point. I never saw him again, no body has ever been discovered and I can but assume that he drowned during our crossing of the Rhine.

SSgt A Waldron, GPR

26th September 1944 06.00hrs

I entered the POW state, like most if not all my peers, desperately disappointed that our venture had failed and at the same time having emerged physically unscathed, I was obviously thankful and thoughtful as to what the future might hold.

SSgt Peter Clarke GPR

Staff Sergeant Peter Clarke G Squadron The Glider Pilot Regiment

SSgt Peter Clarke had been a member of the Royal Army Medical Corps since he was eighteen, serving in the Field Ambulance. Clarke had provided medical services to anti-aircraft batteries in Gravesend before being assigned as medical staff at RAF Manston. Realising his desire to fly, Clarke applied to become Air Crew for the RAF. Although he was successful, the Army no longer allowed transfers.

Instead, Clarke joined the Glider Pilot Regiment in July 1942. Clarke received his Army Flying Wings in March 1943. He was briefed for the D-Day landings, but the day before take-off, Clarke’s co-pilot was taken ill with glandular fever and there was no replacement.

With the first wave of Operation Market Garden, Clarke flew to Arnhem in a Horsa glider with his co-pilot Sgt Arnold Philips. Their load consisted of a mortar platoon of the Border Regiment complete with a jeep trailer packed with mortars and mortar bombs.

Four days into the battle, Clarke started running a regimental aid post in the part of the line which his regiment was holding. Clarke’s previous medical training was essential as he patched up casualties as they waited to be evacuated to makeshift hospitals.

On 25 September, Clarke’s co-pilot, Sgt Arnold Phillips was killed. The circumstances are unknown.

As the order was given to retreat across the river, Clarke chose to stay with four injured soldiers who could not be evacuated.

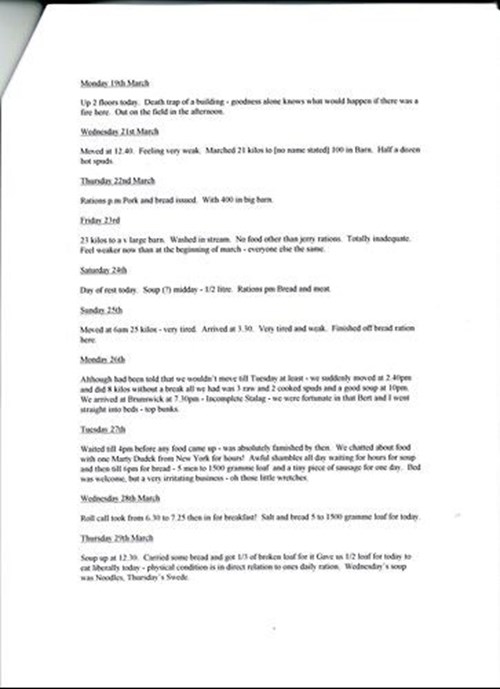

He was taken prisoner of war (POW) by German forces on 26 September. On the night of 30 September, Clarke and two other GPR members attempted to escape. However, they were recaptured the following evening, 13 miles north west of their point of departure by Germans who were hunting deer. Clarke was moved between various POW camps across Germany and Poland before finally being liberated by the American 2nd Army in April. In total he had been forced marched in captivity for over 330 miles.

Peter Clarke was demobilised in 1946 and studied to become a solicitor. He died in 2018 at the age of 96.

26th September 1944 06.00hrs

The ugly reality began to grip me. A fit of deep depression shook me, and judging by other gloomy faces everyone suddenly felt forlorn. With a heavy heart I began my round and broke the unhappy news to the patients upstairs.

26th September 1944 07.00hrs

In total, over 200 soldiers of the Glider Pilot Regiment lost their lives. Many more were captured or wounded during the battle. The Regiment struggled to recover from the disastrous ending to the battle and recruited RAF personnel to supplement their numbers for future operations.

We will remember them.