D-Day Aviators

Introduction

Operation OVERLORD was the codename given to the Allied invasion of German-occupied north-west Europe in 1944. The invasion was launched with large-scale airborne landings and massed beach landings in Normandy, France, on 6 June. This immense assault is now commonly known as D-Day.

The Glider Pilot Regiment

During the invasion, large numbers of troops, vehicles, weapons, equipment and supplies were landed in France using gliders. These aircraft were flown by highly-trained soldiers of the Glider Pilot Regiment.

Air Observation Post Squadrons

As the invasion force advanced, gun fire from artillery batteries and ships of the Royal Navy was directed onto targets by Army pilots in small aircraft. They were serving in Air Observation Post Squadrons and provided aviation support wherever they were needed.

In this feature, we tell the story of six soldiers who were there.

Stanley Pearson enlisted into the 2nd Battalion West Yorkshire Regiment at the outbreak of war, aged just 16. He transferred to the Glider Pilot Regiment in 1942.

On the night of 5 June, he and his co-pilot, Staff Sergeant Guthrie, took off from Tarrant Rushton airfield on Operation TONGA. They were flying a Horsa glider carrying troops of the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry. With two other gliders, they were tasked with capturing a strategic bridge over the River Orne in Normandy.

After casting off from the tug (towing) aircraft, it became clear that Pearson’s glider was overloaded. At a height of about 4,000 feet, they realised they were dropping too rapidly to reach the bridge on their planned course. The glider was being subjected to anti-aircraft fire and the troops on board, preparing for a quick exit, opened a door causing an inrush of air that made the aircraft difficult to control.

Pearson headed for the target using a new bearing but they continued to fall too quickly so, at about 200 feet, he decided to bring the glider into land in a field in front of him. The landing site was surrounded by trees which Pearson and Guthrie had to avoid as they brought the aircraft down, using full flaps and parachute arrester gear. They had landed safely about 600 yards from the bridge.

Pearson was awarded a Distinguished Flying Medal for the operation. The citation for the award reads: “…He carried out his task with great accuracy. Throughout the journey, through his cheerfulness and confidence, he was a great encouragement to his passengers. By his skill and courage, the successful accomplishment of a difficult and hazardous task was made possible.”

Pearson took part in all the major glider operations of World War Two. He survived the war and was discharged in 1946.

Ian Godfrey Neilson joined the Territorial Army in 1938 whilst studying at Glasgow University. He volunteered for flying duty in 1940 and completed his training in August 1941. After an initial posting, he was made the commander of B Flight, 652 Air Observation Post Squadron.

On 6 June 1944, Captain Neilson was tasked with setting up a landing field for his squadron. He recalled:

“A suitable Advanced Landing Ground (ALG) had … to be found, and it would be my job, with a small ground party consisting of Captain AW Keen and five other ranks plus a waterproofed vehicle to get ashore on D Day, reconnoitre possible sites selected from vertical air photographs, and hopefully prepare the best one of three. The vehicle also carried a lot of explosives and my James two-stroke motorcycle.”

Neilson arrived on the Normandy beachhead at about 7pm on D-Day and began his search:

“Having parked the ground party and their vehicle on a disused tennis court… I set off on my motorcycle for the first ALG. This was on the higher ground between St Aubin D'Arquenay and the River Orne and Caen Canal bridges… it was also in full view of the 'opposition' on the east side of the River… and there was practically no tree cover. This would not have been a good choice. I then… went off in a north-westerly direction towards the second possible ALG near Cresserons. Unfortunately, I arrived in the middle of the East Yorks Battalion advance in a south-westerly direction. After a slightly hairy period, they moved on, and I got out of their way. The moral is that one should always follow the line of advance, and not cut across it.

It was by then about noon on D plus 1 and I found the field beside the road to Cresserons. It proved to be a minefield and not for further study. It also had some high trees which would have required a great deal of explosives.

So that left the third possible ALG near the village of Plumetot… after a detailed inspection the fields were acceptable, subject to the removal of a number of obstructions.

At about 0815 hrs on D plus 2 the first five Squadron aircraft…arrived… From then on the Air O.P. 'service' was fully available to the 1 Corps formations.”

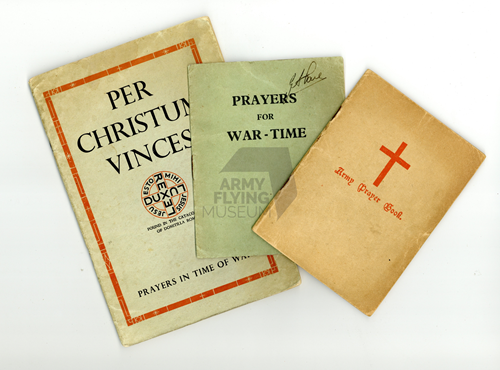

George Pare became a priest in 1939. He was commissioned into the Royal Army Chaplains’ Department in 1941 and was attached to the Glider Pilot Regiment.

He was flown into Normandy in a Horsa glider piloted by Lieutenant Colonel Iain Murray DSO* and Major Brian Bottomley GPR. They took off from RAF Harwell in the early hours of 6 June for a landing zone close to the village of Ranville. Murray recalled:

“Turning in from the coast, the visibility became very poor. A combination of cloud, and the dust and smoke caused by bombing, obscured the ground completely. This may have been a godsend as the [anti-aircraft] fire, although considerable, seemed very inaccurate.”

The glider landed safely at about 3.20am, suffering minor damage.

Chaplains were tasked with providing spiritual and practical help for the wounded and caring for the deceased. Padre Pare checked all the gliders in, and around, the landing zone for the dead and injured. One of the gliders had hit a building at high speed as it came into land and it was assumed that both pilots had been killed. Only when Pare held a mirror to the mouth of one of them, Sergeant ‘Eric’ Wilson, did it become clear that he was breathing and needed medical assistance. He had been trapped in the glider with both legs broken for two and a half days. Pare continued to administer to members of the Regiment and his scrapbooks, held by the museum, contain his hand-written list of those who died in the invasion of Normandy.

Following D-Day, Pare was Mentioned in Despatches for his service with the Glider Pilot Regiment in Arnhem. After the war, he continued his work in the Church of England, retiring in 1977.

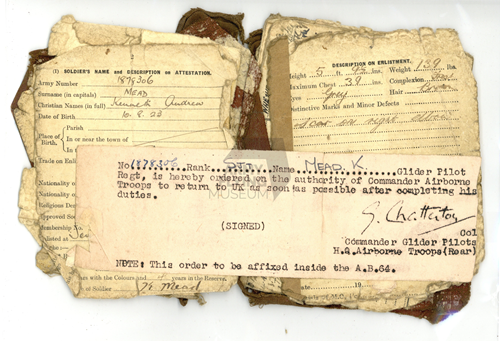

Ken Mead joined the Royal Engineers in 1939 aged just 16. He volunteered for the Glider Pilot Regiment in 1943 and trained as a Second Pilot on Horsa gliders.

On 6 June 1944, he took off, with his co-pilot Staff Sergeant Kenneth Bottomley GPR, from RAF Broadwell on Operation MALLARD. They were one of 258 gliders flying thousands of troops, with their equipment and supplies, into Normandy to protect the flank of Allied forces landing on the beaches. Mead and Bottomley were carrying soldiers of the 1st Battalion Royal Ulster Rifles.

After landing, glider pilots were normally expected to fight alongside the troops they had carried into action but, on D-Day, they were extracted from the battlefield as quickly as possible. There was a scarcity of glider pilots and it was considered essential that they returned to England in case further airborne operations were needed for the invasion. After landing their gliders, the pilots made their way to the nearest beachhead and used their chits to gain priority transport back across the Channel. The majority, including Ken Mead, were back at their squadron airfields in a matter of days.

Sergeant Mead went on to fly into Arnhem in September 1944 where he was wounded and taken prisoner. After the war, he trained to fly small, powered aircraft in Light Liaison Flights undertaking reconnaissance, observation and communications missions. He flew in Germany and received the Distinguished Flying Medal for his service in Malaya.

In October 1959, Mead converted to helicopters and, in 1962, was awarded the Queen’s Commendation for Valuable Service in the Air for locating a group of schoolchildren lost in dreadful weather on Dartmoor. He became a Qualified Helicopter Instructor, a test pilot and a standards officer. He was awarded an OBE and retired in 1978 with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, having completed 7,830 flying hours.

Captain Walby completed his pilot’s course on 3 February 1944 and was posted to B Flight of 652 Air Observation Post Squadron.

In the initial days of the Allied invasion, guns and ammunition were in short supply. They needed to be used to maximum effect and it became essential to provide effective aerial observation for gunnery as soon as possible after the beach landings.

On D-Day plus 1 the Advance Party of Walby’s squadron established a landing ground in fields near the village of Plumetot. This involved removing obstructions such as anti-landing poles, electricity pylons, fencing and a concrete water trough. They messaged the ‘all clear’ to the Squadron at Old Sarum, Wiltshire, and on D plus 2 the first five Auster Mk.IV aircraft arrived. The unit immediately went into action, carrying out 7 artillery shoots that day, followed by a dusk sortie during which an unarmed Auster was engaged by small arms fire from the ground.

Walby flew into Plumetot the following day, along with other troops of the Squadron, and the unit suffered its first loss when Captain E V Pugh RA was fatally wounded. By D-Day plus 4, the Squadron was at full strength and fully operational.

The value of Air Observation aircraft was fully recognised by both sides in the battle. A German report on lessons learnt in Normandy noted: “… the greatest nuisance of all are the slow-flying artillery spotters which work with utter calmness over our positions, just out of reach, and direct artillery fire on our forward positions.”

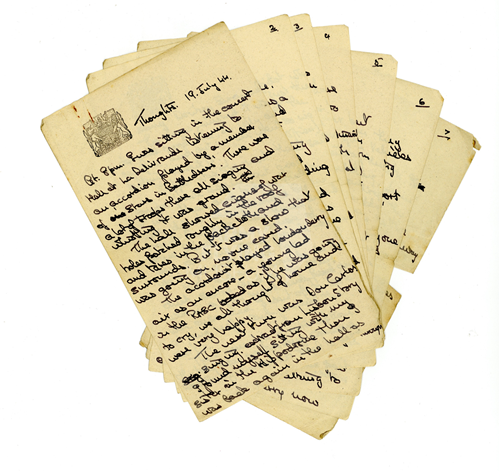

Middlemost Wawn joined the Territorial Army as an 18 year old student at Cambridge University in 1938. On the outbreak of war he joined the Royal Artillery and volunteered for pilot training in 1943. After completing his training, he was posted to 652 Air Observation Post Squadron.

Captain Wawn arrived in Normandy on 9 June, following his Squadron’s advance party.

The following is an extract of the 7 pages of ‘Thoughts’ he wrote on 19 July 1944:

“It’s getting darker now so it’s home for me and I dive down over a field hospital its red cross staring into the sky then over a burnt out German tank, over the river and past a group of soldiers talking to a French girl in a farm they all wave.”

Having landed, he continues:

“It’s 11.30 now and the nightly air raid has started, tracer climbing the sky. … You can hear Jerry now. Down. There’s a whistle. Boom Boom Boom. From where I threw myself on the ground I see flashes and the bombs burst about 500 yards away. … I must go to my dug-out and to bed. He’s not trying for us, that last one was a mistake. The main lot are over the river. I wonder how our chaps are. This war’s strange, very strange.”

In March 1945 Captain Middlemost Wawn was Mentioned in Despatches and in May 1945 he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for his service. He served with 652 Squadron until July 1945 and after the war he continued his career in the Army.