Hamilton E. Hervey MC* - Part 1

The thrilling story of a fascinating RFC Pilot.

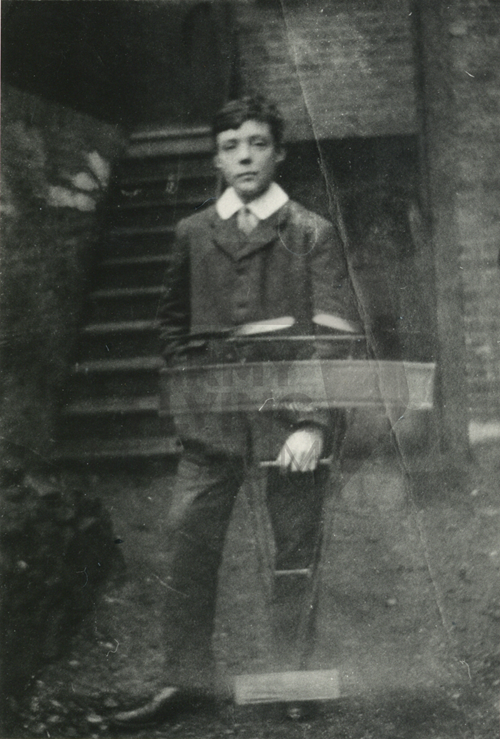

Hamilton Elliot Hervey, later known as ‘Ham’ and ‘Tim’, was born in Portsea, Hampshire in November 1895. His parents were Hamilton Law Hervey, a magistrate in the Indian Civil Service, and Edith Kathleen Bayley, daughter of a Colonel in the Madras Infantry. Hervey was the second child of six and the family grew up in Portsmouth, before moving to Brighton.

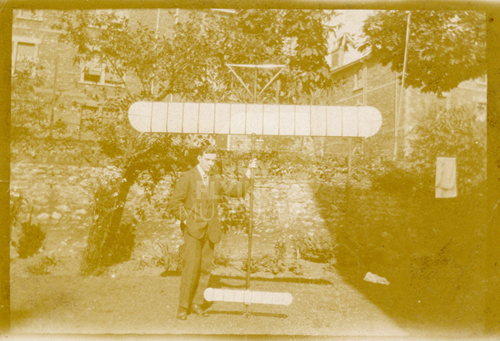

Growing up Hervey had a great interest in model making, specifically aircraft. He began making models aged 10 and by his mid-teens he was reported to have been designing and building 50 model aeroplanes a year! He attended school in Yorkshire during which time he joined his first aeronautical club, the Brighton & District Model Aero Club. His interest was piqued further when in 1912 he took a ride in a Graham White Box-Kite and the following year he went up in a BE2 at the Army Aircraft Factory at Farnborough. He was also a regular feature in the popular aeronautics’ magazine, Flight, between 1911 and 1914, where many of his models and designs were shown and discussed.

After leaving school he joined the British and Colonial Aeroplane Company (later The Bristol Aeroplane Company) as a pupil carpenter. When the war broke out in 1914, he did not wait long before joining and enlisted on 16 September, aged 19, into the Royal Flying Corps (RFC). He worked initially as a mechanic, specifically a rigger, specializing in maintaining and repairing aircraft and moved up to the rank of 1st Class Air Mechanic. He served with No. 12 Squadron, stationed at Netheravon, and moved to France in September 1915 where he worked as the rigger for Louis Strange, a pioneer in aerial combat.

In March 1916 Hervey began his training in observation and aerial gunnery and was subsequently granted a commission. He was posted to No. 8 Squadron, at La Bellevue, France whose main role was carrying out reconnaissance, contact patrols and artillery spotting. It is here that he served with famous aviator Albert Ball, carrying out artillery shoots and a balloon attack over the German lines at the Somme.

Ball was posted back to No. 11 Squadron in August but Hervey stayed on with No. 8. He flew regularly with Capt G. W. Parker and in mid-November, while out on artillery patrol, they spotted a lone Albatross Scout. They engaged the aircraft, as Parker and Hervey’s had been modified to hold an over-wing Lewis Gun. After a long duel over the lines they forced the Albatross to land. Landing alongside, they stopped the pilot, Lieutenant K. H. Büttner, destroying his machine. It was the first Albatross Scout captured intact by the British and, as was custom at the time, a trophy was taken from the aircraft. Hervey chose the airspeed indicator.

Later that month Hervey returned to England to carry out his pilots training at the Central Flying School. Fortunately, he had already received around 30 hours flying training from his Flight Commander and was able to go solo after only a day of training.

In December, he received notice of his award of the Military Cross (MC) for his work as a gunner and a few months later he was awarded his pilot’s certificate. Following this he was posted to No. 60 Squadron near Arras which operated the Nieuport Scout.

When Hervey arrived, he was thrown right into the action in ‘Bloody April’ and the squadron suffered heavy losses. 60 Squadron found themselves going up against one of the best aces of the war: Von Richthofen, the ‘Red Baron’, and his ‘Circus’. Hervey recalls:

‘…one particular ace pilot was rumoured to be a women, due to a long flowing scarf worn around the pilot’s neck.’

The scarf wearer was the ‘Red Baron’ who Hervey encountered on 7 April 1917:

‘I was attacked at 10,000ft, the top of the joy stick was hit and the instrument panel was shot away also, although I was not aware of it at the time, the rudder control wires were hit. In trying to take avoiding action with steep turns, due to the loss of rudder control I went into a spin. The machine came out of the spin of its own accord after 6,000ft but I was being followed by the German machine and once again, trying to take avoiding action, went into a second spin coming out at 900ft, four miles on the German side. The engine was hit but still functioning and as I levelled out I saw, through a gap in the clouds, the German turn away presuming me hit and I was able to return to base.'

It was the policy of General Trenchard, head of the RFC at the time, to be aggressive, meaning fighting and pursuing the enemy on the German side of the lines. This led to a significant number of aviators being taken Prisoner of War (POW). The following day, Hervey once again found himself in aerial combat. He set off at 08:35 am in a Nieuport Scout equipped with a Lewis gun, along with several others from the Squadron. He and another pilot were given the job of cover, flying at a higher altitude while the rest of the flight pursued an enemy aircraft. The two cover pilots were attacked by several German aircraft and Hervey managed to evade being taken down. In the ensuing chaos he found himself alone:

‘I saw a number of British FE[2bs] being attacked and went to help them. However, I was hit by anti-aircraft fire [which stopped the engine] and I was too far over the lines to get back and came down near a German artillery dugout.’

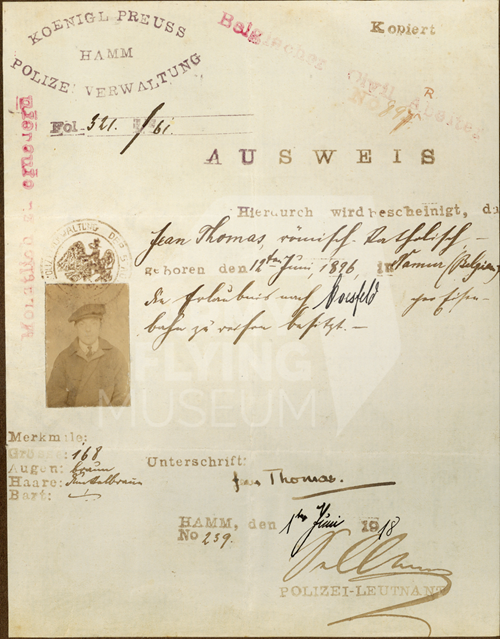

After landing he was taken into the German dugout and given some lunch before he was sent to a nearby farmhouse where he was to await transportation to Douai, where the Germans were based. His time fighting in the war had come to an end, at least in the conventional sense. He was interrogated and placed in solitary confinement before he and a larger group of captives, including Victoria Cross winner William Leefe Robinson, were put on a train to Karlsruhe POW Camp. His family knew before the War Office and his Squadron did that he was still alive after being taken captive because he sent a cheque through the Dutch embassy to get cash for the POW camp. They then informed his parents. Hervey was soon moved to Freiburg where, after several attempts to escape, he succeeded with Robert ‘Mac’ Macintosh , William Leefe Robinson, Arthur A. Baerlein, C. M. Reece, and F. C. Craig. They then separated into two groups. After several days on the run Hervey, Macintosh, and Craig were captured, as were the other group. He and some of the others were eventually sent to Fort Zorndorf, a much more secure camp where serial escapees were sent. Attempts to escape here were put in motion but it was too secure. Despite this, fake passports were created, specifically for Belgian farmers working on German farms, for when they did escape. Hervey was to be disguised as a ‘Jean Thomas’, though he never had the chance to use it.

This is the end of Part 1 of our 'Hamilton E. Hervey MC' blog post series. Come back again for Part 2 which describes more of Hervey's daring escape attempts, his involvement in MI9 and with military gliders in WW2, as well as his career post-war and retirement.

Bibliography:

Army Flying Museum Collection

Fedorwich, E. K., ‘Foredoomed to Failure’ The resettlement of British Ex-Servicemen in the Dominions, 1914-1930, unpub, 1990.

Fry, H., MI9: A History of the Secret Service for Escape and Evasion in World War Two, 2021.

Hervey, H. E., Cage Birds, 1940.

National Library of Austrlia, Trove

‘Rigger to Pilot – 2Lt H. E. Hervey MC*’, Cross & Cockade, Vol. 14, No. 4, 1983, pp. 153-160.

Trove, National Library of Australia, Newspapers & Gazettes: https://trove.nla.gov.au/

Wright, L., The Wooden Sword, 1967.

Written by Kyle Thomason, 2023